|

| How do we preserve digital information? |

Cohen and Rozenweig have lots to say about creating historical collections online, from the reasons for building one in the first

place (flexibility, accessibility, collaboration and longevity) to what lends

itself to an online collection and what doesn’t. A site focused on, say, submissions from WWII veterans

probably won’t attract much interest, where a site on 1980s Casio digital

watches (collected by uber-geeks the world over) definitely will. They tackle the thorny problem of how to

solicit contributions, pointing out the paradox that “to build a collection,

you need a collection.” Ultimately, it’s

about building trust, being part of a community of interest and (surprisingly),

not worrying too much about “qualitative concerns,” which the authors have

found to be a non-issue for the most part. The authors include a helpful case study using their

own September 11 Digital Archive, which follows all of the best practices they

suggest.

Having covered the basics, the next stop was the

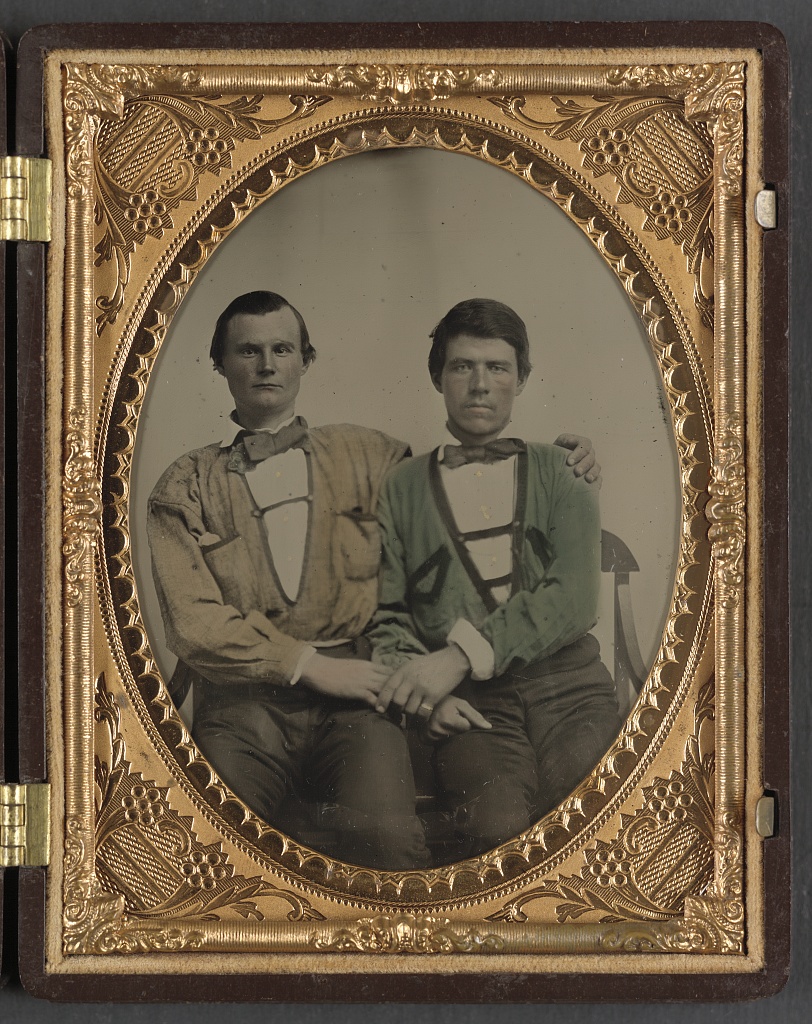

gigantic Library of Congress Digital Collections. I dove into Chronicling America and Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, which contains images of Confederate and Union soldiers

and their wives and children, all available in JPEG and TIFF. In addition to organizing and displaying all

this great stuff, the LOC also includes a set of tips for preserving digital

information: identify what’s

important, decide what to keep, Export what you want, organize the collection, make copies and manage them in different places.

There’s even a downloadable brochure.

Having covered the basics, the next stop was the

gigantic Library of Congress Digital Collections. I dove into Chronicling America and Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, which contains images of Confederate and Union soldiers

and their wives and children, all available in JPEG and TIFF. In addition to organizing and displaying all

this great stuff, the LOC also includes a set of tips for preserving digital

information: identify what’s

important, decide what to keep, Export what you want, organize the collection, make copies and manage them in different places.

There’s even a downloadable brochure.

Last, we

looked at Flickr’s collaboration with the LOC called “The Commons.” It’s filled with a huge variety of images

from two collections (“1930s – 40s in Color” and “News in 1910”) that are posted

with “no known [copyright] restrictions”.

By this, the LOC is indicating two things: “either there was a copyright

on the image and it was not renewed,” or “the image is from a late 19th or

early 20th century collection for which there is no evidence of any rights

holder.” They are clear that this “not

mean the image is in the public domain, but [it] do[es] indicate that no

evidence has been found to show that restrictions apply.”

|

| Awkward Civil War Era Photograph. |

The other

interesting feature of The Commons is the ability to add tags and comments to

images. While this seems to have great

potential for illuminating what might otherwise be lifeless photos, there are

some concerns about the proliferation of tags and the extraneous

comments that people post. I can

certainly understand how the latter might be a problem, but I looked at the

last ten images posted and not only were there no goofy comments, but every single

one of them in fact had at least one relevant, helpful post. Perhaps those particular images just haven’t

been up long enough to attract the oddballs.