|

| Remember These? |

This week's readings covered the important (but complex) topic of

digital preservation. Usually I'd address them in order because that's how my reptilian brain works best, but this time I'm going to start with the

last offering,

The Polar Bear Expedition site from the University of Michigan. This is an important reading, as it came with a detailed analysis in the form of an article

("Interaction in Virtual Archives: The Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections Next Generation Finding Aid"), which brought up the idea of

interactive digital archiving. The goal was to take all of this digitized material from the little-known

U.S. intervention into the 1917 Russian Revolution and create a sort of virtual archival community centered around four principles: places, common ground, awareness of other users, and spontaneous, informal encounters. The Polar Bear archival site allows users to place bookmarks, leave comments, browse, search, create user profiles and, most interestingly, view "link paths" that reveal what other users have searched for. The innovation here is that instead of emphasizing the archivist's role, the site makes the users interaction with the materials central, positing that it the user, not the archivist, is responsible for creating

meaning during that interaction.

|

| It's inevitable. |

With that in mind, it's easy to understand why preservation of digital collections would be important. The Wiki article

"Digital Preservation" covers the basic issues around the longevity of digital information and the efforts to preserve it. The attempt to find common ground is the sticking point, and one can see with the Open Archive Information System and the Trusted Digital Repository Model, which attempt to standardize seven "attributes":

compliance with the reference model for an Open

Archival Information System (OAIS), administrative responsibility, organizational

viability, financial sustainability, technological and procedural suitability,

system security, procedural accountability. The basic strategies by which this can be accomplished are through migration of data to new environments, replication of data (making sure it's in more than one place), refreshment of data on two types of the same storage medium and emulation, which attempts to reproduce the data on a different operating system or storage medium. The specific digital preservation tools (TRAC, DRAMBORA, the European Framework, nestor, and PLATTER) include certification programs designed to ensure compliance to minimum standards. "What is Digital Preservation" clarified many things that the Wiki article left cloudy, like the meaning of "long-term", what should be preserved, and why we should work at preserving anything in the first place.

|

| "Bring out your dead!" C'mon. You know the movie. |

"'Digital Dark Age' May Doom Some Data" makes clear why these are worthwhile efforts. Jerome P. McDonough asserts that the vast quantity of digital information and the speed at which environments are changing presents the potential for loss. The striking example was magnetic tape, on which the government stored the 1960 U.S. census data. Just fifteen years later, there were only two computers in the world that could read it. The analogy is obvious, I think. McDonough suggests that we need to move away from proprietary systems and specific file formats and to a more open framework that is less vulnerable to obsolescence.

|

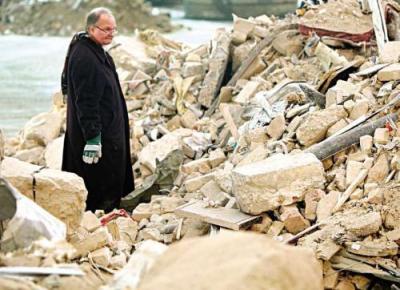

| Sorting through the pile of data. |

The last article, "Digital Archivists, Now in Demand" gave me hope that I won't be a highly educated homeless person at the end of this MA program. The most interesting thing about the article was the assertion that IT people are not ideal as digital archivists, as they tend to simply add storage space rather than sifting through information like historians do.

After all this reading, I think I might go listen to some cassette tapes from the 1980s. You do know what those are, don't you?

No comments:

Post a Comment